DEATH!

DEATH!

In The Haymarket

We want to feel the sunshine;

We want to smell the flowers;

We’re sure God has willed it.

And we mean to have eight hours.

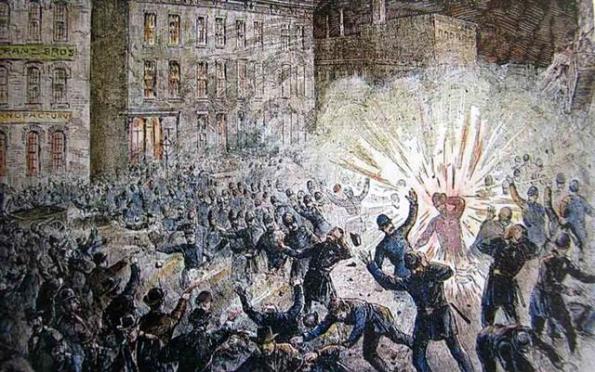

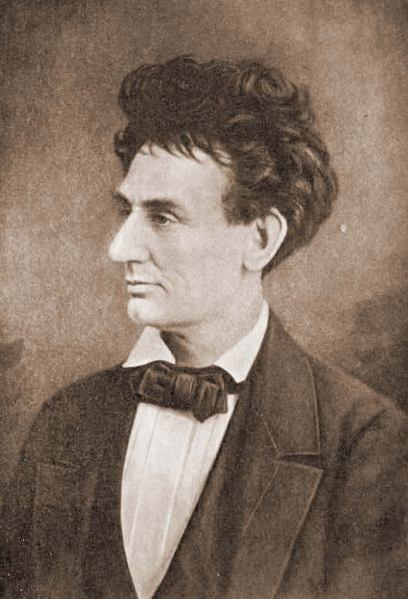

On May 1, 1865, the body of Abraham Lincoln arrived in Chicago on its way back to Springfield for burial. Fifty-thousand mourners came to pay their last respects to the Great Emancipator on his final visit to the city. Carl Sandburg wrote that amid the gloomy procession were, “native-born Yankees and foreign born Catholics, blacks and whites, German Lutherans and German Jews—all for once in common front.” The city was unified in their grief over the dead president; however, the next couple decades would see many challenges to that solidarity. On another May 1st, twenty-one-years later, a worker’s protest demanding and eight-hour workday would escalate into a disastrous affair that would deal a blow to social advancement in the midst of Gilded Age America.

In his book, “Death In The Haymarket,” historian James Green reveals the rise of the first great labor movement in post Civil War America, and a bloody event at Haymarket Square, in Chicago, on May 4, 1886. A subsequent trial culminating in executions of working-class agitators would distance the business class from wage earners, both foreign and native born. The setbacks that followed would take the worker’s movement decades to recover.

Chicago was a bustling city enjoying a decisive competitive edge over all other industrial rivals because of its access to eastern markets via the Great Lakes, and to the Midwest farms and forests through the Illinois & Michigan Canal to the Mississippi River. During the Civil War the city’s slaughterhouse and packing industry boomed after securing many lucrative military contracts. As Saul Bellow wrote, progress was written, “in the blood of the yards.” By the end of the Civil War, it was the destination of every railroad system west of the Mississippi all the way to the Pacific. The never ending need for wage workers would lead to the influx of European immigrants with Chicago’s population doubling in the 1860’s. In the 1880’s nearly 250,000 souls migrated to the city looking for work and were no doubt part of the 800 freight and passenger trains leaving and entering the city daily.

Green explains that Chicago’s population grew 118 percent in the 1880’s which was a rate of growth five times faster than that of New York City. The city’s foreign-born population reached 450,000 which was larger than the total population of St. Louis, or any other city in the Midwest. As could be expected the new arrivals were overwhelmingly represented by impoverished peasants, or refugees fleeing foreign oppressors. With the supply of available labor at a premium, profiteers would see their net value increase far faster than the average yearly wage. This would undoubtedly lead to class tension, with animosity revealing its ugly side in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. In that year, Mayor Carter H. Harrison, found the spark that would ignite a fire of class hatred that would envelop the city for the ensuing decade. His name was John Bonfield, and as police captain he would write the text on how to use “disciplined brutality” in suppressing worker rebellions.

In his call to action against the railroad strikers, Bonfield led the assault with one observer noting, their “clubs descending right and left like flails.” During the melee, the captain personally beat down an elderly man who did not respond to his order to fall back. Two men were clubbed unconscious, with one suffering permanent brain damage. The following day Socialist militant, August Spies, spoke to a crowd of several thousand workers, denouncing Bonfield’s “vicious attack” on the citizenry and according to one report, “advised streetcar men and all other workingmen to buy guns and fight for their rights like men.” When leading citizens called for Bonfield’s dismissal he was retained, “on account of his political influence.” To the fury of organized labor, a few months later the ill-tempered captain was promoted by Mayor Harrison to be chief inspector. The battle lines had been drawn for years to come, and as Green explains, “During the fall of 1885 a cloud of class hatred hung over Chicago; it seemed as thick as the smoke that darkened its streets.”

We’re summoning our forces

Shipyard, shop and mill;

Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest,

Eight hours for what we will.

May 1, 1886, was the beginning of several days of peaceful protests and demonstrations at the McCormick Reaper Works, until a small group of unarmed picketers were shot and killed by Chicago police. The next day, May 4, a mass protest led by anarchists was held at Haymarket Square on the city’s West Side. Again police entered the scene to disperse the crowd as the meeting began to wind down. Out of the night, an unknown individual (and today we still do not know who it was) threw a dynamite bomb in the direction of the police, killing one immediately and fatally wounding six others. The police fired their handguns in a wild frenzy killing at least three protesters and wounding many others.

The Chicago Tribune published an exaggerated and unfounded account of the events in the following day’s edition with other newspapers and magazines nationwide following its lead. Mass hysteria would result in police taking extraordinary measures in a reign of terror that would arrest the rights of all “alien” workers throughout the country, but especially in Chicago. As Green puts it, “the first Red Scare was in effect,” and hostility toward Chicago’s immigrant population came from every possible demographic. The eight hour movement lost all momentum and labor reform came to a screeching halt. A sensational trial followed that summer, and a stacked jury found seven anarchists guilty, resulting in their condemnation for their part in “assisting” the still unknown bomber. The labor movement and social reform would be put on hold.

First Log Cabin Republican?

Wanted To Know About Abe

But Were Afraid To Ask!

Abraham Lincoln is perhaps the most iconic individual in American History and folklore. His image is adorned by monuments from Mt. Rushmore to Washington, D.C.; and one can hardly ignore his continued presence in everyday situations such as purchasing a product with a five-dollar-bill and getting back change with “Lincoln head” pennies. He is considered by most to be our greatest president who saved the Union, ended slavery, and wrote two of our most cherished speeches in the Gettysburg Address and his Second Inaugural. With all these reminders, “Honest Abe” in ingrained in our minds and in our hearts, yet most of what we know about him is based more on legend than on fact. What we sincerely know best about him we really don’t know at all. Or it is exaggerated, or based on what others with an agenda would like us to think.

With such a legacy, it’s no wonder that people are curious, and occasionally anxious about the truth regarding our sixteenth president. Gerald Prokopowicz’s book, Did Lincoln Own Slaves?, is a careful catalogue of the thousands of questions he was asked over the course of nine years as resident scholar of the Lincoln Museum at Fort Wayne, Indiana. Some the questions are shocking, some are thought provoking, and some are just plain stupid. Equally, some of the answers are surprising, but most could probably be deduced by using common sense.

The litany of inquiries include just about everything from, “Was Abraham Lincoln’s last name really Lincoln?” to “Was Lincoln’s corpse ever stolen?” So what does the book really tell us about Lincoln? First off, he was a hard guy to understand, even by his closest friends, which may account for so many interpretations. Secondly, there are things we can never really know because the answers would all be based on conjecture. So in reality, Prokopowicz’s book may provoke more questions than answers.

Some of the most enjoyable answers came from questions about Lincoln’s athletic ability. Aside from the author’s belief that he possibly could have been the first white guy before steroids able to dunk a basketball, Lincoln’s storied reputation as a wrestler is fascinating. Ironically, his only known match happened in 1831 as a new arrival to his adopted hometown of New Salem. Much is revealed about Lincoln’s character in that event in that he was unafraid to take on the town’s known bully Jack Armstrong. No one is really sure who won the match, but he did manage to earn the respect of Armstrong and his gang of thugs, the “Clary’s Grove Boys.” Honest Abe was versatile enough to be competitive in just about every activity he tried, including “town ball,” which was an early form of baseball only with bases laid out in a square and not in the form of a diamond. Lincoln’s strength was revealed early in his youth when he worked as a rail splitter, which involved pounding a sledge hammer on an iron wedge to split logs into four equal sized fence posts. During the Civil War, he would “show off” his incredible strength by holding an axe horizontally, gripping only the very end of the handle, a feat no soldier could duplicate.

Since Lincoln has been baptized posthumously by so many so many modern revivalists, it was refreshing to read from an expert that evidence of his religiosity is mostly unsubstantiated. Although he may have used the words, “God” or “Almighty” in many of his addresses, this may have been politically motivated to appease the audience of his day. Certainly, he was fluent in biblical terminology, but the same can be said of his verse for Shakespeare. Both can probably be attributed to his voracious appetite for reading, especially literature that could explain difficult situations with poetic articulation. Without question Lincoln was a spiritual man, but his belief system was that of a deist who believed in “Providence” as a product and not as the guidance of a higher power. According to Prokopowicz, in New Salem, “Lincoln associated with freethinkers who doubted the divinity of Jesus, and he wrote an essay mocking the idea that Jesus was the son of God.” Of course this manuscript was tossed into the fire by his friends to “protect his budding political career.” According to Mary Todd Lincoln, “who ought to have known, he was not even a Christian.” Of course, it is only coincidence that he was born on the same exact day as Charles Darwin.

The most intriguing questions and answers were those concerning Lincoln’s sexuality; basically, “Was Lincoln gay?” This is no small matter since according to Prokopowicz; this is the number one Lincoln question of the twenty-first century! Surprisingly, the author skirts around the question by suggesting that there was no such definition identifying one as “gay” in the course of Lincoln’s era, although he admits that Lincoln may have engaged in “homoerotic” activities. Historians have never denied the “emotional intimacy” between Lincoln and his lifelong companion Josh Speed based on their many revealing letters to one another. But let’s be serious, Lincoln and Speed lived together and shared the same bed for four years! The rail splitter also had a close personal relationship with Captain David V. Derickson, who was assigned as his bodyguard on his frequent retreats to the Soldier’s Home during the Civil War. The two spent so much time together, and were so reclusive, that rumors were rampant within soldier’s camp. Many claimed that when Mrs. Lincoln was away, the two slept in the same bed chamber with Derickson often seen wearing the president’s nightshirt. So based on the known evidence, and the lack of outright denials from reputable historians, Honest Abe probably was at least partially gay by today’s definitions. Not that there is anything wrong with that.

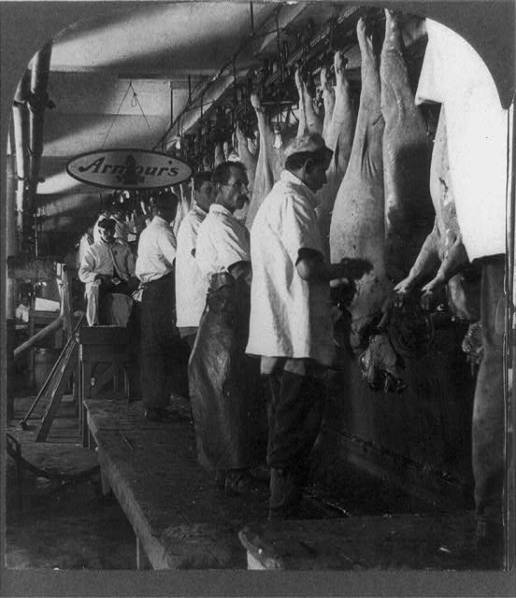

Everything But The Squeal

Ever since Upton Sinclair’s, “The Jungle” first came into print in 1906, it has been has been used by generations as a tool to illustrate the corruption of the beef industry in turn-of-the-20th-Century Chicago. No doubt readers of every genre have cringed at the torturous descriptions of wailing animals and the spectacle of filthy, disease ridden disassembly lines producing every product imaginable including lard, sausage, glue, and fertilizer. Even President Theodore Roosevelt was shaken by this story and questioned whether-or-not tainted meat products were responsible for deaths in the Spanish American War. The Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 were the result of The Jungle. And although, the book’s notoriety may have made Sinclair famous, the resulting healthier meat products and increase in the number of vegetarians were unintended consequences.

Sinclair’s goal in the novel was to create an awareness of the greater human tragedy of urban slums and the factory systems throughout the world. He once wrote, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” For this reason the book’s effectiveness as a work of propaganda may not have been completely realized.

Sinclair was an ardent Socialist, and his goal from the beginning was to bring attention to the plight of workers. The book was commissioned by the largely circulated Socialist newspaper, Appeal to Reason, with the goal of bringing attention to working-class liberation. He made his intentions clear when he first arrived in Chicago to research for the book 1904 and declared, “Hello! I’m Upton Sinclair, and I have come to write the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the labor movement.” And although the book is a work of fiction, its content was based on indisputable facts about the ubiquitous graft and corruption dominating Chicago at the time. Only the names were changed to protect the innocent.

Sinclair used as his prop, an unfortunate and misguided group of Lithuanian immigrants to showcase the inequities of capitalism or the “wage slave” system. The story is seen through the eyes and mind of Jurgis Rudkus, a boldly ambitious young man, who despite his incredible strength and work ethic becomes a casualty of greed and avarice at a place called “Packingtown.” The villains of the story are the American Beef Trust, the corrupt political machine of Chicago, and capitalism altogether.

Rudkus brings with him to America, his aging father Antanas, his young fiancé Ona, and members of her family including her mother Elzbieta. When they arrive in Chicago Jurgis seeks employment in Packingtown, and because of his brawn, immediately finds work to the chagrin of the hordes of onlookers who fruitlessly wait daily for the opportunity of employment within the slaughterhouses and processing factory. Before long the realities of many desperate situations set in, and despite Jurgis’ pledge to “work harder,” the family goes deeper into a cycle of debt and poverty until every capable member of the family is forced to work in deplorable and dangerous conditions for paltry wages. The biggest contributor to their demise was being conned into purchasing a home they could not afford.

Before long, Ona dies in childbirth because they cannot afford a doctor and eventually their only surviving son drowns in a mud hole in a street near their tenement boarding house. In exhausted frustration, Jurgis abandons the family entirely and leaves for life as a hobo in the heartland. Eventually he returns to Chicago where he takes up every means of employment available; from being a criminal to a political operative, which in most cases by Sinclair’s description, are one and the same. His political shenanigans lead him back to Packingtown, where many betrayals leave him unemployed and eventually imprisoned. Ultimately, he ends up as a high risk beggar on the streets where nightly he faces death from freezing or starvation.

One particular evening he went indoors to join an audience listening to a speech, something he did frequently as a way of seeking refuge from the cold. This time, however, he was spellbound by a charismatic Socialist orator whose words seemed to be describing the agony of Rudkis’ travails on a personal level. From that point on, he became a Socialist “Comrade” with his life finally taking a positive turn and becoming all he had hoped for in coming to America. This is the part of the story that was supposed to be the epiphany of Sinclair’s book, that Socialism was the answer to all societal evils. Unfortunately for Sinclair, most reader’s minds were already more fixated about not eating Tubercular beef than on the plights of exploited workers. So, based on Sinclair’s original intent of promoting Socialism, his work of fiction was less effective as a work of propaganda.

Philly Skyline from U-Penn

“It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts” –Doris Lessing

First off, I want to extend a sincere thank you to professors Harris and Rees and to the “man behind the curtain” Scott Whited for their expertise in planning and coordinating such an awesome educational odyssey; and of course, for allowing me to be a part of the experience. The quantity and the quality of our adventure proved that it took a an enormous degree of foresight.

Where do I start? After so many years of studying and teaching the “facts” about American History, I now regret that I couldn’t have made this trip 20 years ago. I feel like a college student studying Spanish and earning a master’s degree, then going to Spain and realizing that you really didn’t know anything. More than anything else, I’ve learned that “reading” about something without “experiencing” it, falls short of the lesson. And that is why this trip was so special for me, I experienced things on such an elevated level that I can relate them to many other events in history. It’s like studying the history of the Nile River so intensely, that you can better comprehend the history of every other river in the world.

An important, and independently observed lesson for me, was the realization that there are so many heroes in our history who do not have their portraits on American currency, or their names on documents…and are essentially lost to history. They were the ordinary people who made enormous contributions and remain nameless, probably because they were illiterate and couldn’t record their lives. For example, who were the countless slaves and servants who built the nation’s economy through their sweat, or the cooks and washerwomen who saved more lives at military encampments than the better known physicians? Who were the grunts that went on foraging missions, or the ferrymen who led the Continental Army’s horses and cannons across the icy Delaware River? Who were the grave diggers at Valley Forge or the “unknowns” at so many burial grounds? Each of them had a face and a story, and even though we do not know their names, the place we call America couldn’t have happened without their sacrifices.

Those “extraordinary” ordinary Americans are still with us today, like Pat Stallone and Ada Fischer who work less for their paychecks than for their love of preserving history. Or the many citizens of Philadelphia who were so congenial in answering the many questions from a “wandering tourist,” or bus driver named Bob, who would buy Starbucks for a group of passengers he hardly knew. And the teachers, who gave up their free time and the conveniences of home to become more informed for the benefit of their students.

I can’t end this post without telling of an experience at the Kitchen Kettle Village in Lancaster County on the very day we visited the Amish in 100 degree heat. After waiting in line outside a lunch counter for about 20 minutes, I was told I could not get my lunch because they only took cash and all I could show was a check card. Suddenly a woman in line behind me presented a $10 bill and said, “I’ll get it,” and proceeded to pay. I told her to wait until I found an ATM but she insisted, “don’t worry about it, it’s too hot, enjoy your lunch.” I told her that it was such an awesome thing to do, and that I would “pass it on,” –and I will. She was yet another great American who’s name I will never learn, but whose deed I will never forget.

Even though Valley Forge was one of the first historical sites we visited, I have waited until now to write my post about it. To be honest, it has taken me this long to figure out exactly where I stand on the many accounts related to that historic winter encampment of 1777-1778. And to be really, really honest, I’m not so sure I’m even sure about what I’m sure about. Now, anyone who has managed to continue reading this far, don’t quit on me now, I can explain. But first I have to go back to when I first learned about Valley Forge in primary school.

The story went something like this:

- Worst winter in American History

- Secluded wilderness

- Troops were starving, but still patient

- British lived in comfort in Philadelphia during same period

- Some foreign guy named von Steuben worked wonders with the troops

- George Washington prayed often in the wilderness

- Americans kicked butt at Monmouth and cruised to Yorktown

The legend didn’t change much from junior high through college, but the trouble is that most of the story just isn’t true. But then again, some of it is, and that is what historiography is all about. Two of the books we had to read to qualify for the Philadelphia trip were not very complimentary of the version given above. In “Founding Myths,” by Ray Raphael, the winter of 77-78 was one of the warmest on record and the troops were not starving, and certainly not very patient. In “Valley Forge Winter,” by Wayne Bodle, the author confirms the Founding Myths account, but goes further (in excruciating detail) by lambasting the secluded wilderness idea and minimizing the impact of von Steuben. So…my new opinion was set, the Valley Forge winter story was a sham; but then I visited Valley Forge and Monmouth with our tour group and my mind was changed again!

At Valley Forge Park, our tour guide did little to dispute the challenges by Raphael and Bodle, but he didn’t have to; he simply explained the logistics of the park and what it was like during the encampment. Today there is an impressive hardwood forest at the park, but the ranger explained in the winter of 1777-78 there would not have been a single tree standing within a three-mile perimeter from the center of the park. This area would have included the Potts House where the command center was located. All were cut down by the army to build the 2,000 or so wooden huts or cabins used that winter, and to build items like carts, wagons, boats, and bridges; and there was the ever present need for firewood. That alone tells me that the soldiers were all very busy and working with a measure of discipline and cooperation since clearing a forest with primitive tools is not an easy task and the cabin replications we saw were really quite crafty. These are things that kept the army fit, both mentally and physically and something that could not have been duplicated by the Brits in Philadelphia.

There was also death at Valley Forge, lots of death with estimates ranging up to 2,000 men. This amounted to more fatalities than from any single battle of the war and it was not from starvation as legend tells, but from diseases like dysentary and influenza. These are the type of sorrowful conditions that build character and determination, and create anger toward your enemy. Not so in Philadelphia.

And then there was Baron Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben, who arrived at camp in February and immediately began transforming a group of state militias into a permanent standing army. Von Steuben not only increased the speed of troop movement and musket reloading, he created what became known as the “Blue Book” of military encampment which included the standards of sanitation that would still be used 150 years later. While others question the impact of von Steuben, just looking at the arrangement of the encampment clearly shows he knew what he was talking about.

And then there was the parade grounds, where on May 6, 1778, Continental troops put on a show for congressional dignitaries in celebration of the new French alliance. It must have been a proud spectacle for troops and for officers alike; and a confidence builder as the spring and the new campaign rapidly approached. This was the place where the American Army was built, and today’s military must agree since West Point plebes still pay a pilgrimage to the parade grounds every September.

After spending two weeks in Philadelphia and seeing where the British spent the winter, I’m convinced the morale must have been uneasy, particulary since they were so insecure about the intentions of the local population. From what I learned at the Philadelphia visitor’s center, few people except for the most hardened loyalists shed a tear when they evacuated the city. Their army certainly couldn’t have emerged into the spring 1778 any better fit than when they first arrived. The same can not be said of the Continental Army at Valley Forge.

The test would come at the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778, where in my opinion the “new” Continental army came out clearly on top, and for a variety of reasons (read my blog post from June 8, 2008). I believe this was the turning point of the war and it was all made possible by the winter encampment on the banks of Valley Creek.

In conclusion, I have come to my own conclusion about the importance of the Valley Forge Winter. No, the legends are not true, but the facts are more impressive, and to some extent, I now consider myself a primary source along with many others who have shared their opinions on the topic. I have learned through historiography.

Lesson Plan

How would I teach about Valley Forge? I would start by having students read chapter 5 from “Founding Myths” and compare it to the text book version, and to other versions they have already learned from their previous teachers, parents, scout leaders, etc. I would even ask if any elders in their families could provide us with a text book from many years ago; perhaps they exist in the public library. I would then ask them to formulate their own opinions and try to explain why they are different from what they had previously learned. Their findings would be reported to the class in many different forms; from oral and written reports to quizes and posters they may create. I would also ask that they research why there are different versions of the same events in most of our history, and how someone’s agenda may sometimes shade the facts. They can research how to find the truth about any topic and how they can practice historiography.

One of the many fun events on our trip was the opportunity to see an exhibit of the pirate ship Whydah at the Franklin Institute of Science Museum, or “The Franklin” as referred to by locals. Actually it is the world’s first exhibit that includes authenticated pirate treasure, including ingots of gold and silver and treasure chests of jewelry and coins…lots of precious coins! But the real treasure was the story of the ship itself, and its incredible crew that went down in a storm just off of Cape Cod in 1717 along with the booty of 54 ships the buccaneers had plundered.

The Whydah (pronounced WIH-dah) was first launched in 1715 from London as a slave ship that took part in the infamous triangular trade that traversed the Atlantic with human cargo. The name Whydah was taken from the west African trade city Ouida where slaves were loaded and taken to the Caribbean. In 1717 it was taken over by pirates led by captain “Black Sam” Bellamy who led a successful crusade of robbery at sea before sinking just 1,500 feet from shore in Massachusetts. The firepower was in evidence with the actual weaponry on display, including swords, pistols, cannons, and ammunition; all enclosed within a life sized replica of the ship recovered in 1984. Sadly we were not allowed to take pictures.

Along with artifacts there was a glimpse of the every day life and responsibilities of a pirate crew, including that of navigators, surgeons, cooks, and carpenters; it was a very busy scene. The makeup of the Whydah was typical of many pirate ships and could easily be described in two words; diversity and democracy. The crew included Europeans, American colonists, Native Americans, and Africans who were experiencing their first real taste of freedom. There was even a nine-year-old boy on board named John King, who had joined the crew against the wishes of his mother. All had chosen their unseemly occupation simply because there were no better options available to them in life. There were no women crew on this ship, although their service on pirate ships is well known to history.

The authority of a pirate ship represented the purest form of democracy ever known to the world. The captain was elected by every single member of the crew and could be replaced with another vote at any time. All received an equal share of the treasure, regardless of rank, and there was no social structure based on race, gender, occupation, past conditions, or even age. The nine-year-old had the same income as the captain!

It was a lucrative, but risky occupation with few pirates ever dying poor, or from old age. The life of a pirate was short, but sweet, and so it was for the crew of the Whydah who met their end just three years after assembling. Even though they were criminals, their fate still represents a sad ending with all but one of the survivors of the wreckage meeting the hangman’s noose. Their corpses were put on display and left to rot as a deterrent to others who may have had ideas of chosing piracy as their career.

The most macabre portion of the exhibit was the boot and actual fibula of the King boy who didn’t survive the wreck. The tiny leg bone, found in a woolen stocking, was proportional to that of a child his age. The bell, which must have rang repeatedly during the violent storm, clearly shows the inscription “WHYDAH” and is enclosed in a glass case filled with sea water to prevent rusting.

June 13, 2008

…”for those who were here gave their lives that that nation might live.” — Abraham Lincoln

The Battle of Gettysburg has often been called the greatest man made disaster in American History, and it remained so until the Bush v Gore Supreme Court Decision of 2000.

It was extremely appropriate that the visit to Gettysburg was the last of our planned trips on this incredible educational excursion. After all, none of our group’s scrutiny to this point, including all aspects of the Declaration of Independence, Revolutionary War, or Constitution would have amounted to much if the Union Army had not won the battle in and around this small community on July 1, 2, and 3, 1863. As Lincoln said many months later, these brave men “gave their lives that that nation might live.”

This was an exciting day for me since I have studied and taught about the turning point of the Civil War for many years, yet no book, statistic, movie, or documentary, ever prepared me for what I saw with my own eyes. It was a humbling and haunting experience that made me feel small, yet important because I am a proud citizen of this country and one who appreciates the sacrifices made by those who came before me.

Who can guess what might have happened had the results the battle been different? Would the north have given in and allowed for two nations? There was tremendous political pressure in the north for the war to end and this battle could have been the positive turning point for the Confederacy. After all, Robert E. Lee was on a roll with string of victories and seemed invincible. Bloody draft riots were emerging in New York City and the British were always on the horizon as a potential southern ally. What would have happened to the Constitution, would it have become a useless, meaningless peice of paper? And what about African Americans, would they ever have been free, and if so, to what extent? Could there have been future wars between the two new countries? One thing for sure America could have never become a world power and we ourselves would have been enslaved to the evil empires that emerged in Europe and Asia in the 20th Century. Without a doubt, the results of this battle saved the United States, and perhaps the free world.

As pleasing as this trip was for me, I have to admit that I was disgusted with the countless monuments glorifying Confederate bravery on the battlefield. Perhaps markers showing the positioning of Lee’s divisions would have been appropriate, but to see exalting and lionizing statues of the enemy was insulting! These were not Americans fighting for state’s rights as many would have you believe, they were the worst enemy our country has ever known and they were fighting to preserve human bondage. They spit on our Constitution and stepped on our flag, and killed more Americans than Hitler ever could have hoped for. And when they murdered Lincoln, they danced in the streets. There should not be a statue of Lee at Gettysburg, he was the worst traitor in American History; Benedict Arnold pales by comparison. How sad it is that the “Federal” government has allowed this to happen. It only strengthens the determination of today’s hypocrites who like to wave the Confederate flag and say that it is part of their heritage. This is an affront to those brave Union troops who gave their lives to save the Union, and to Lincoln. How offending it must be to African Americans who are still recovering from centuries of slavery and from the Jim Crow laws created by the descendants of those same confederate officers and soldiers.

This wall represents the “High Water” mark of the Confederacy. This was the spot where, on the third day, Pickett’s Charge ended. Things would go downhill for the South and General Lee from this point until the end of the war.

Reflecting pond at Winterthur

June 12 — 2008

I enjoy watching the Antiques Road show but have often found myself asking out loud, ” who in the world would pay $150,000 for a an old rocking chair?” Well now I know; people like Henry Francis du Pont, whose Delaware seasonal estate we visited today. I say seasonal because he would only have been found here in the early spring, and would probably have been in the Hamptons by June, and in one of is many other mansions in the winter. But this estate in the Brandywine Valley named Winterthur, was the place he chose to call home and I can see why.

There are over 300 rooms filled with a priceless collection of 85,000 masterpieces of antiques and Americana and a renowned research library with manuscripts and rare books dating back to the 16th century. Nicolas Cage may have been able to break into the Smithsonian in “National Treasure,” but I doubt he would have made it passed the men’s restroom in this place. The security is intense and I’ll never forget the icy stares from the grumpy old lady who led our tour group, with taser in hand ready to zap you in the neck if you took just one step into the next room without permission.

I am not usually one who goes gaga over museum peices like furniture or fine porcelain, but I have to admit I was a little overwhelmed by some of the items, especially the fine wares used by Martha Washington to serve special guests. My favorite part of the building was the spiral staircase that was disasembled from another home by du Pont’s carpenters and brought to Winterthur.

But my favorite part of the day was undoubtedly my tram tour and walk through the 60 acre naturalistic dreamscape which could easily be called America’s Garden of Eden. Besides being an expert on early American furniture, du Ponte was a renowned horticulturist and he designed this acreage with a spectacular arrangement of rare trees, flowers, waterfalls, and reflecting pools; and an enchanted fairy-tale garden for kids of all ages. This was a place where someone could have informed me that I was just about to die, and I would have said….well, okay. This was a place that words cannot explain and pictures cannot describe, and one that I will not soon forget.

In descending order are photos from the Winterthur Garden: Flower bush, close-up of flowers, forest, playhouse, mushroom playhouse made from the trunk of a dead tree…

Independence Hall Bell Tower before dusk

June 11 — 2008

Tdoc1oday we were commisssioned with the joyful task of a self-guided walking tour of historic Philadelphia. This was great for me since I knew I could not be labeled with the infamous tag of “lollygagger” for not keeping up with the group. You see I have a habit of overextending my “moment” at every historical site, which includes reading every possible word on a placard and asking anyone who will listen, every imaginable question. For these reasons, my tour guide (me) was very accommodating.

I started at the most rational place, the visitor’s center, which had many interesting items and helpful people. I was able to watch two videos with the best one being about the diaries of different teenagers of many walks of life starting at the moment the Declaration was signed and then through the long war that followed. Some were in favor of the movement, others opposed, and as always, some were unsure. It also covered in great detail the British occupation of Philadelphia (while Washington was with troops at the winter encampment at Valley Forge). This was something I needed to see more of since it was a topic I knew little about. Especially helpful were the illustrations of the city at the time and how the occupation and the evacuation was viewed so differently through the eyes of loyalist and patriots alike.

“Constitution Cow”

Perhaps this photo will get my students at Pueblo County interested in the Constitution!

From there I completed a hike through an area I wanted to see since the first day, Dock Street, which is the only street in Old Philadelphia that is not at a right angle. It is in the place of where Dock Creek used to be and where it is alleged that Willie Penn first departed ship and touched land in Pennsylvania. It was such an important location that the original city of Philadelphia was designed from the creek outward. It was a convenient docking point for merchants and traders who made the city wealthy and there are many tales of shady visitors like Blackbeard and Captain Kidd who frequented the ubiquitous taverns on each bank. Eventually the many tanneries, smith shops, and slaughterhouses along the creek made the water so polluted and foul-smelling that the area was eventually sealed off and covered. Today all that remains is a chalk line placed by the National Park Service showing what used to be the path of the creek (small photo, top left).

One of the most touching sites on my tour was Washington Square and the Tomb of The Unknown Soldier of the American Revolution. It is actually the last resting place for thousands of unknown soldiers from the war who died from wounds and sickness and were buried en masse. The site includes the bones of many other unknowns who departed life in Philadelphia including condemned criminals, slaves, and many victims of the horrific yellow fever plague in 1793. The only joyful thing about the park was that it was a site where African American’s, both free and slave, gathered to sing traditional songs in their native tongues and to engage in African dances. No doubt these were rare moments of mirth for a people trying to forget the difficult life the new world had brought to them. In one of my “lollygagger” moments I sat on a bench for a long period of quiet reflection trying to imagine all the rollercoaster events that took place on that small piece of land.

Finally, my tour brought me back to Indepencence Hall where I sat on the grass on the back side of the building; which was actually the front side in the summer of 1787 when delegates met to figure out a new Constitution. It was late in the afternoon and there were few visitors present which allowed me to quietly visualize the days of the convention and the great men who met in secrecy for many hot months just inside those brick walls. My imagination allowed me to see nosey Philadelphians peeking through the windows, and as I looked at the door I could see James Madison and the Virginia delegation, and other delegations of other states stepping outside for a breath of fresh air, and discussing in private the issues that would best represent the needs of their state while allowing for a strong national government. I imagined delegates bidding good night as they left each day on their way to a local tavern or to their homes to write a letter to their families who must have seemed worlds apart. As the shadows began to cover the bell tower of the building, it was a serene moment for me. This was the experience I was hoping for ever since I read Carol Berkin’s book, “A Brilliant Solution.” I was not disappointed; it was a great day for me.

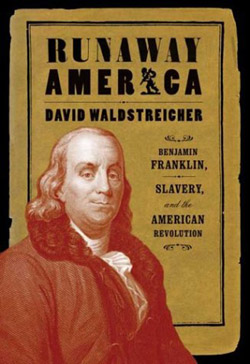

Wow! Eleven days into the trip and we finally found someone who could say something bad about Benjamin Franklin. Our first lecturer of the day was David Waldstreicher, a professor at Temple University and the author of “Runaway America,” a book that brings into question Franklin’s reputation as America’s antislavery founder.

Wow! Eleven days into the trip and we finally found someone who could say something bad about Benjamin Franklin. Our first lecturer of the day was David Waldstreicher, a professor at Temple University and the author of “Runaway America,” a book that brings into question Franklin’s reputation as America’s antislavery founder.

According to Waldstreicher, Franklin is always viewed as being opposed to slavery, and by looking at his “official” record how could anyone come to a different conclusion. For example, the following information about Franklin is well known:

- 1787 – Joined the Pennsylvania Abolition Society

- 1789 – Petitioned against the slave trade to congress

- 1790 – Ridiculed southern state defenders of slavery

- 1776 – While in France, he allows Parisians to create an image of him as an antislavery Quaker

- ——No mention of slavery appears in his autobiography

And who could question his personal travails, himself having been a runaway from the abusive indentured servitude of his older brother in 1723. Having lied about his servant status to a ship captain he eventually found his way to Philadelphia and a lucrative career as a printer. Within 25 years he transformed himself from a servant to a colonial gentleman.

But what is rarely ever mentioned is the “unnoficial” record about Franklin, starting with how he attained his wealth. His Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper became profitable by the advertisments for runaway slaves and slave auctions. By the 1750’s there were hundreds of such ads in every edition and ironically the work in the printing office, both skilled and labor intensive, was accomplished mostly through slave labor.

Franklin’s chief complaint against George III in the Declaration of Independence is where the King has, “excited domestic insurrections amongst us.” This part was specifically written in Franklin’s hand and refers to the crown’s support in the cause of abolition in the colonies. Incidentally there were no provisions in his will for the freeing of his slaves upon his death.

Our second great speaker of the day was Dr. Robert Engs, a history professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and a Civil War expert.

Mr. Engs started his lecture with what he called two great American myths:

- That Mr. Lincoln freed the slaves

- The south suffered a decade of negro rule following the war

Engs supported the argument that the slaves freed themselves, first by stifling the southern economy during the war by being less than productive on the plantations, and second, by serving gallantly for the Union Army. He added that by 1861 there were four major questions in the north regarding southern blacks.

- Will they rebel?

- Will they want freedom?

- Will they fight for it?

- Will they know what to do once they are free?

Of course the slaves provided their “YES” answer through their actions, before, during, and after the war. And it seemed as if the northern commanders were the ones who were unsure about what to do since they were still enforcing the fugitive slave act after winning battles early in the war. Engs said that the slaves knew the war was about their freedom and they resisted attempts to flee the plantations until the safest and most opportune moments emerged. Once it was clear they could run away safely, there were precision evacuations to the safety of the northern armies where slaves were more than willing to work hard on behalf of thier liberators. It is estimated that over 400,000 escaped laborers contributed to the Union Army in various ways with about 12 to 15 percent of them consisting of enlisted men.

As for Lincoln, Engs contends that his motivation for the war was not to free the slaves, but to save the union. And the Emancipation Proclamation may have been intended to neutralize any European forces (especially Britain) who might have supported the south in the war. Once the Union made emancipation an issue, there would be an obvious distinction between the combatants that hadn’t existed before.

My favorite story of the day came from Mr. Engs and was about a former slave reflecting on his condition. He reflected that during the time he was a slave, he worked hard, but had no responsibilities and no worries. But now that he was free he still works hard, and has a wife and children to provide for, only now he has lots of worries, but he said that in the end, “I still chooses freedom!”

John Brown

Today our group traveled to the American Philosophical Society and the Atwater Kent Museum where we gained exclusive access to some American treasures rarely seen by outsiders. On our first stop at the APS library where we had the priviledge of viewing many important documents, most of which were associated with the founder of this exclusive club established in 1743, none other than Benjamin Franklin himself. The building contains over 250,000 journals and books including the largest folder of Charles Darwin’s works outside of England. Among the many documents was a letter sent to Franklin’s son from Franklin’s grandson across the English Channel via hot air balloon. Of course this was the first “air mail” letter in world history (Jan. 1784) and just happened to have the Franklin family involved.

Another pair of amazing “white gloved” documents were two letters, one which must has challenged the spirit of Washington at a time when he should have been basking in glory as a victorious commander-in-chief. On June 12, 1784, when the war was already over, Washington sent a letter to three Virginia representatives of the new congress requesting support for Thomas Paine who was rumored to be in financial distress. Washington’s heartfelt letter explained that Paine’s motivational writings helped to inspire the revolutionary cause, and that he should be awarded some measure of compensation such as a veteran’s pension. This was not requested by Paine, but done on the good graces of Washington with respect for a man he considered a friend.

Fast forward about 10 years later and Paine is arrested and imprisoned in Paris by radicals of the French Revolution. Paine then fires off an inflamatory letter (1795) accusing Washington of doing nothing to secure his release. Paine’s letter is extremely rude and impersonal and addressed to “The President of the United States” and starting with a simple, “Sir.” Who knew? I always thought they were best friends for life, but a new side was revealed in Paine. Perhaps he only wrote pamphlets like “The Crisis,” which sold over 500 thousand copies for profit and not for more noble causes. Nonetheless, Washington must have felt slighted by a man he thought he knew well.

In the main hallway we were able to see many treasures, including the original printed copy of the Declaration of Independence, and a draft by  Jefferson that had many lines crossed out by members of the congress who made corrections (click thumbnail to read Jefferson’n note to Franklin requesting a review of his draft). We saw the only existing document that has the signature of four presidents; Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. We were also treated to the journals of Lewis & Clark and many other items I will not soon forget.

Jefferson that had many lines crossed out by members of the congress who made corrections (click thumbnail to read Jefferson’n note to Franklin requesting a review of his draft). We saw the only existing document that has the signature of four presidents; Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. We were also treated to the journals of Lewis & Clark and many other items I will not soon forget.

At Atwater Kent, we learned of the powerful Abolition movement in Philadelphia; our class was in the same room where Frederick Douglass met with many who were sympathic to the cause. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society founded in 1775 is the oldest such organization in the world, primarily because of the Quaker influence. Franklin joined the society which gave it prominence, although his motivations are unclear since his newspaper made most of its profit through advertisements of all aspects of the slave business. Needless to say, the entire movement was controversial, mainly because of the geographical location of Philadelphia, and its proximity to many slave states. The worst case event started with the burning of Pennsylvania Hall in 1838, a building which was to serve as a home base for many radical anti-slavery groups. It was destroyed by a mob just three days after opening, beginning a wave of violence against African Americans in the city. In a print from the Philadelphia City History Collection (Atwater Kent Museum), it shows a crowd watching the structure burn while the city fire department only hoses water on an adjacent building. That same evening, a black orphanage is burned to the ground only blocks away. For more information on this topic, go to GOOGLE and enter quest for freedom philadelphia.

We were shown artifacts related to some incredible individuals, including the best portrait I’ve ever seen of John Brown (pictured top of page) and his very own musket he had in his possession at Harper’s Ferry.

Amish farm through barn window

MY PERSONAL “GREAT AWAKENING”

Today was a personal religious experience for me, not in any biblical sense, but in my spiritual reconnection to the land. I remember as a child watching my mother prepare the ground for a garden, then watching in amazement as squash seeds fulfilled their purpose, sprouting through the brown earth only days later. This was not for a science project, but out of necessity, since we were very poor and food we could grow was food we could live on. Both parents left this world before I was 10, but the memories return as I till the soil each spring; not so much these days for the crop, but for spiritual sustinence that comes with remembering my happiest days.

It was heartening to watch the Amish work the land today, in the same ways that they have for countless generations; in a place where children walk barefoot in the soil and where horse power is defined by its the true meaning. I saw families bond through sweat and traditional communities prosper, notwithstanding the all-too-visible barriers of the modern world; far away from what the majority of Americans call the “real world.” And how wrong we are! The real world is not cell phones and traffic jams; or fast food and road rage. We define our happiness by the size of our flat screen TV and our success is measured through online banking. The children of our society have no connection to our heritage, show little civic responsibility, and have no realization of who we are and how we got here. So much for the real world.

The Amish represent Thomas Jefferson’s dream of an agrarian society where the spiritual dimension of farming was to promote self-reliance and moral integrity. Of course we live in the 21st century and humanity has evolved through technology, but it doesn’t mean we should forget how food gets to the table; and we should not lose the respect we owe to the land and to those who work it.

As history teachers we must feel obligated to make our students reassociate the goals of our past with the needs of our future. They must experience that important affiliation with the soil, even if it means planting a plot behind school grounds. Only then can they realize that it’s the land more than anything else that makes us a great nation. We may suggest they visit Lancaster County in Pennsylvania some day. It would make them proud to be Americans and make them understand that we can do better than growing corn to power SUV’s.

When we were treated to an Amish communal meal today, we experienced a taste of American History. Our beautiful guide Ada, who was 90 years young, helped us reflect on the elders we all miss, and to the fabric that makes our heritage great. When the children of Abner and Katie sang the words that said, “we will all be friends forever,” I felt a kindred connection. We are all of the same soil.

“94 degrees — heat index 102 degrees” —Weather.com

It was so hot today, I followed Sheila around just to get the cold shoulder!!! But the good news was that it played into one of the most authentic, lifelike, and realistic interpretive trips any self-respecting history teacher could have asked for. The battle of Monmouth (June 28-1778) is famous for a plethora of reasons and the oppressive, sweltering heat on that historic day is one of them. Our park historian and field guide stated that, according to official records, the temperature was identical to that on the day of the battle and in fact there were as many British casualties due to heat exhaustion as from American fire.

It should be noted in the official record of the world for today, that a brave contingent of historical pilgrims hiked with our guide in a patriotic 2 mile excursion through this sultry wilderness while a crew of “sunshine patriots” shrank from the service of their country and elected ride back to the visitor’s center in an air-conditioned bus.

Monmouth was the first battle following the winter encampment at Valley Forge and was the direct result of General George Washington trying to slow and harrass British forces under General Sir Henry Clinton who was moving to join other forces in New York. Early in 1778, Benjamin Franklin secured a treaty with France and the British command knew the Delaware River would soon be filled with French war ships. Clinton had no choice but to evacuate Philadelphia and retreat northward with Washington on his tail.

It seems like every battlefield visitor’s center has a placard stating that this was the “turning point” in the war, but this one may really have some merit. For example, this was the first occasion where Continental troops matched or surpassed British regulars in all aspects of warefare including tactics, discipline, strategy, and battlefield resolve. There are many scholars who have questioned the importance of Baron Von Steuben and his training of Washington’s troops at Valley Forge, but according to our expert historian/guide at Monmouth, the Prussian’s winter visit was invaluable.

This battle was also important in that it may have been the elimination round for Washington’s nemesis, General Charles Lee, who until this point was gaining support in the continental congress in his insurgent pursuit of becoming commander-in-chief. A disagreement about orders arose and Lee publicly disrespected Washington, thus leading to a court martial and ultimately to his dismissal from military service. The troops looked upon Lee with disdain and may have engaged this battle with greater intensity to embellish the reputation, and to reassure the command of their beloved Washington. The outcome of the firefight, with the greatest artillery barrage in the new world to that point, produced much needed political and military objectives. Washington and his army would gain the respect of the continental congress and our French allies, while the British command and their loyalist allies were now painfully aware that the page to a new chapter in the war was turning. For these reasons, I disagree wholeheartedly with many historians who say that the battle of Monmouth concluded as a draw. I walked that ground, and it is the property of the United States Government. Had Washington been routed that day, it would be part of a British national park with statues of General Clinton on the grounds.

“MYTH-INFORMATION”

I know Ryan is still struggling with the devasting fact that Molly Pitcher is a mythical person, but then again she is still reeling from the time her parents explained that her brother was an only child. I pity the girl when someone tells her the facts about Santa.

“FIELD” NOTES

On our hike through the park, the ranger warned us of an assortment of biting insects from gnats to deer ticks, but I feared not! For they were but insignificant little microbes when compared to the fearsome savage restroom creatures that have taken command of our dorm room.

Today we were on the SEPTA Subway again, only this time it was not as confusing as Father’s Day at an FLDS compound. With precision and alacrity our forces were soon stationed at the National Constitution Center where cutting edge pedagogical training would soon commence. Everyone was excited to see and hear Carol Berkin again and she did not disappoint!!!

As expected we were treated to an educational experience that was as entertaining as it was informative. Today her topic was about the myths surrounding the Constitution, and its creators, a topic where she certainly is an expert. Her focus was not on the traditional tales of the convention, but on the admirable qualities of the founders, including their moments of doubt and their fragile level of confidence; traits not usually associated with these reputable men. According to Berkin they were obsessed with the dangers of power, to the extent they were actually fearful of themselves…that really is a commendable quality. As for the men themselves, she alluded that there were only about 7 of them in attendance that could really be labeled as “Brilliant,” with Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris leading the list. She said that most were just of average intelligence, but with the education and worldly experience needed to engage the challenges before them.

After Berkin, we were guided on a tour of the fabulous facility while simultaneously competing with the decibel level of thousands of bothersome juveniles also in attendance. There were many amazing interpretive exhibits covering every category of great accomplishment in American history, all made possible by such a powerful, yet flexible Constitution. It was especially gratifying to walk through the statuary hall to mix and mingle with the extraordinarily detailed lifelike figures of the founders. From the looks of it, George Washington was a real bad ass with an intimidating physical presence. It’s easier to see how he was such a great leader when you stand right next to him, or below him based on his size. If they had just put he and King George III together in a cage for just a few minutes, this whole revolution thing could have been decided a whole lot quicker, with a lot less cost and the least amount of turbulence! Once again this was another great day in Philadelphia.

Nassau Hall

Princeton’s only building in 1777

“Parade with me my brave fellows, we will have them soon”—George Washington

Today, as with General Washington, we traversed the Delaware River a couple of times. Except that our movements were extremely less eventful and not as heroic as those made by the father of our country and the brave soldiers who followed on that bitter cold morning of January 3, 1777. Washington’s crossing may have saved our country and “this day in history” ranks second in American importance only to my birthday, which also took place on January 3 a couple hundred years later. But I digress…

The Battle of Princeton was a pivotal point in the war, because it gave beleaguered American forces a new confidence that victory against the mighty British forces was actually possible; something that until that point was doubted by most, including Washington himself. The victory at Trenton just days before came at a crucial time for Washington since desertions were plentiful and many enlistment periods would be ending at the start of the new year. Washington came up with a bold plan or “strategery,” as G.W. Bush would say, with hopes of engaging the enemy with the element of suprise. Knowing British forces were stationed in, and around Princeton, Washington ordered his forces their direction on the evening of Jan. 2, leaving a small distractive force at Trenton as decoys to throw the British off. At dawn the next morning the Americans engaged the enemy in a fierce battle with Washington leading the charge through the center of the battlefield, disappearing and reemerging back from the cannon smoke. In the battle General Hugh Mercer was wounded and bayonetted repeatedly until assumed dead after refusing to surrender, however, he died 9 days later in the home of Thomas Clarke near the battle site.

The firefight continued all the way to the town of Princeton and to where British troops were hiding at Nassau Hall, which at that time was the only building at Princeton University. It was reported that Alexander Hamilton took particular delight at bombarding the structure since he was denied admission to the institution a few years earlier. The decisive victories at Trenton and Princeton eliminated British forces under General Charles Cornwallis from New Jersey and had the much desired effect of inspiring 8,000 new troops to enlist in the Continental Army. Of course many hardships would still follow with the next winter’s encampment at Valley Forge.

Our interpreter at the Clarke House was masterful at describing the battle and the troop positions leading up to the combat. With just a little imagination you could sense the panic in the air, feel the thundering of hoofbeats, and smell the burning gunpower from cannon and musket fire. He also corrected a couple of false legends of the events noting that the Hessians were not drunk and helpless at Trenton and General Mercer did not die at the trunk of a giant oak tree which was named after him.

Later in the day we had a walking tour of the University of Princeton and the community itself. Among the most intriguing sites was the deliberately inconspicuous an modest home of Albert Einstein pictured below.

Monday, June 3

What an awesome day in an awesome town! I’ve studied American history since Moby Dick was a guppy, but to actually be where it all happened was overwhelming. As anyone reading this can see I am just learning to blog and am having some difficulty with my pictures, but very soon I will have this site looking better. But that doesn’t mean I did not have an American experience and feel the karma of all who came before me.

My experience actually started Sunday, the moment we left the ground from DIA and headed east. I still have a sore neck from staring out the window the entire distance of around 2,000 miles or so. I could see the Missouri River, and in my mind’s eye, could see the Lewis and Clark corps of discovery working their way upstream in their keel boats; and of course this was just a tributary to the mighty Mississippi which would come up next. Within minutes I saw the the Monangahela and the Allegheny join together to form the Ohio River and I could see Pittsburg within the confluence. Throughout the way there where incredible highways, bridges, cities, nuclear power plants, etc., all mixed in with the patterned farm squares below. At the same time I was glancing at a screen via an internet connection that showed the flight path of our aircraft, plus 24 channels of direct TV. What a great country! And to think, all of this would become possible because of events starting in 1776 in the very city I was traveling to.

In Philadephia, it was incredible to see just how far we have come in such a short time based on World History perspectives. Perhaps most striking was the diversity of the population with every race and culture represented, with most of them here for the same reason as our group… to see where it all started. The following day an African American man would clinch the Democratic nomination for president of the United States, and there is a chance he may have as his vice presidential running mate a white woman. Wow! To think that just a little over 200 years ago in this same town, the founding fathers, including George Washington, had slave quarters as part of their housing rentals…and women could not vote. Everything these great men did then, made all that our nation represents today possible. I don’t think that in their wildest imaginations they could have dreamed of what was to come, and much of what followed was the result of unintended consequences. But freedom and democracy are for real, and it started here in Philadephia.